In

Bird by Bird, which sits mockingly on the bookshelf of every unpublished writer, Anne

Lamott explains her theory of "

Shitty First Drafts." She says that "All good writers write them [shitty first drafts]. This is how they end up with good second drafts and terrific third drafts."

An undeniable truth of writing: Writing is rewriting.

For most of us, several drafts are required to make any piece of prose readable. Several more passes are required before the electricity we hope to conduct begins to spark. A few more drafts and then you've got something. Finally we need all sorts of proofreading tricks (from reading aloud to reading sentences backward) before your baby is ready for a reader.

Of course, there are exceptions. We love to believe that we are all Jack

Kerouacs typing mercilessly into a roll of paper towels that we send straight to our editor to retype and pass on to the publisher. But those are alcohol, methamphetamine-soaked dreams.

On the Road had to be revised, and so will every solid cover letter, love note or magazine article you ever write.

Of course, there will still be errors or poor word choices or sloppy syntax in nearly any article or story or kidnap note you release to the world. Just look at the paperback version of the

Kite Runner and note the several repeated words and other petty slips. But you, the writer, can take refuge if you did the work.

Of course, there will be times you can take no refuge in your diligence. You'll write a stirring critique of Bush's foreign policy and realize that you used the wrong "there". You might leave out a "The" in the title of your term paper. And unfortunately, one day you will write

a blog post about the role of sentences, and the result will be such a mess that a commenter will wonder if English is your first language.

That last example, of course, happened to me. A fine

reddit commenter "Munificent" found my post on sentences and wrote a

skilled critique of my post, which at many stages of my life would have made me suicidal. Thankfully, he's found me post-

Eckhart Tolle, and I was able to laugh most of the pain away.

His criticism was also much easier to take because it was generally astute and correct. Some of his points were about style, but he also pointed out a sourly obvious grammar

faux paux in my second sentence. All and all, I think he missed what I was trying to say, and, of course, my sloppiness was to blame.

I was attempting to argue that grammar rules should be secondary or third-

ary to the idea conveyed by a sentence. Sometimes a fragment will offer a reader more than a "complete" sentence ever can, while a meandering compound or complex sentence provides a writer a chance to reveal contradictions or embed a subtle critique.

Of course, the idea that the role of sentences is mutable isn't original. That's why I used examples from classic writers like Dickens, Tolstoy and Nabokov to make my case.

Even these safe choices were abhorred by Munificent, who saw me trying to say something new about these authors. I wasn't. I was trying to show readers how to steal some of tricks of the greats. But apparently that comes off as pretentious when you can't write one sentence that's lucid enough to be read.

Even in shame, a lesson.

I think I've learned from Munificent. He reminded me of the importance of revision and the necessity of clarity. And he also humbled me, as if life hadn't done that enough.

So the lesson today is that occasionally letting your shitty first drafts out into the world isn't always such a bad thing. You just better expect some of the shit to blow right back into your face.

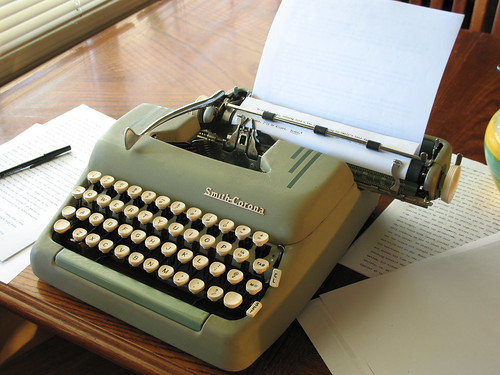

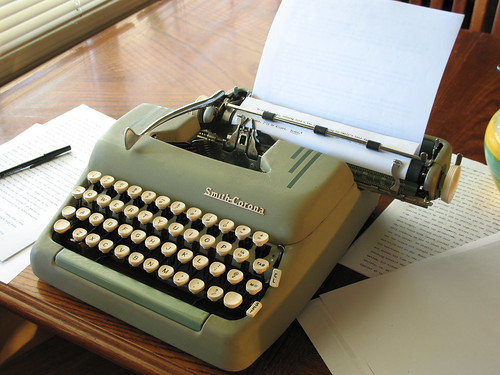

Picture by mpclemens.